The energy transition is no longer just a policy debate — it’s a practical challenge reshaping how we design, build, finance, and operate infrastructure. With governments committing to net-zero targets and developers under pressure to decarbonise, energy is becoming central to project planning. At the same time, reliable and affordable energy is now recognised as crucial for national competitiveness and long-term economic development.

In this context, Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) are gaining traction as a commercially viable way to secure cleaner, more reliable energy. A PPA is a long-term contract between an energy buyer (the off taker or buyer) and a power producer (the generator or seller), typically locking in electricity at a fixed or formula-based price over a defined period (e.g., 10 years).

Once the domain of utilities and energy majors, PPAs are now being explored by a diverse range of players — from infrastructure and energy developers to asset owners, government agencies, and even day-to-day energy users and retailers. In some cases, developers are adopting commercial models similar to public-private partnerships (PPP Contracts) to structure these projects more effectively.

As the use of PPAs continues to grow, so too does the need to understand their practical implications — from contract structure and risk allocation to long-term performance. In this article, we’ll explore what Power Purchase Agreements are, how they work, and why they’re becoming increasingly relevant across the construction industry.

What is a Power Purchase Agreement (PPA)?

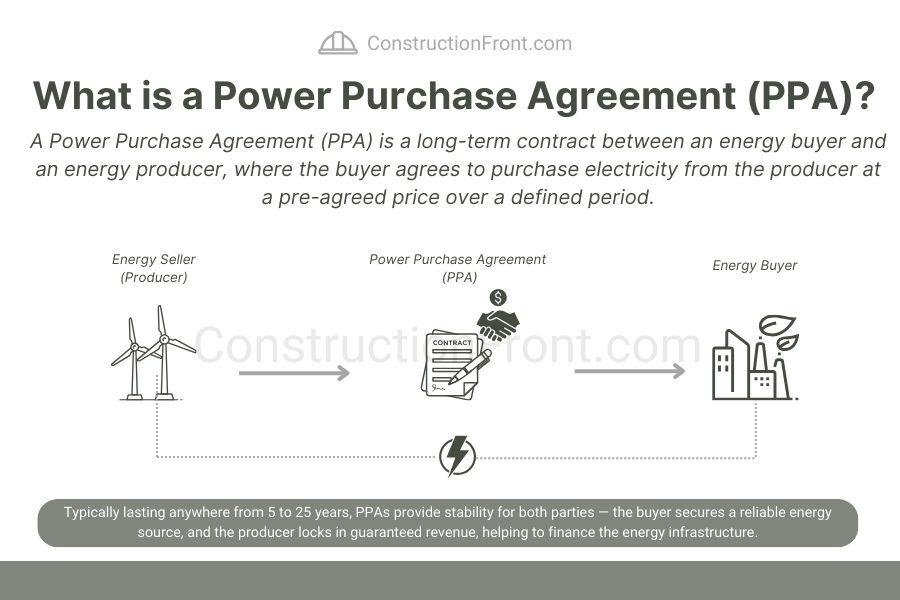

A Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) is a long-term contract between an energy buyer and an energy producer, where the buyer agrees to purchase electricity from the producer at a pre-agreed price over a defined period. Typically lasting anywhere from 5 to 25 years, PPAs provide stability for both parties — the buyer secures a reliable energy source, and the producer locks in guaranteed revenue, helping to finance the energy infrastructure.

In a typical PPA, the terms are tailored to suit both parties. The buyer may agree to pay a fixed price for electricity for the duration of the agreement or a price indexed to inflation or market benchmarks. The seller, in turn, commits to delivering a defined quantity of energy — usually measured in megawatt-hours (MWh) — over the contract term.

These agreements offer buyers a degree of protection (“hedge”) from energy market volatility while providing producers with the commercial certainty needed to secure investment and debt financing for energy projects.

Key Advantages of PPAs

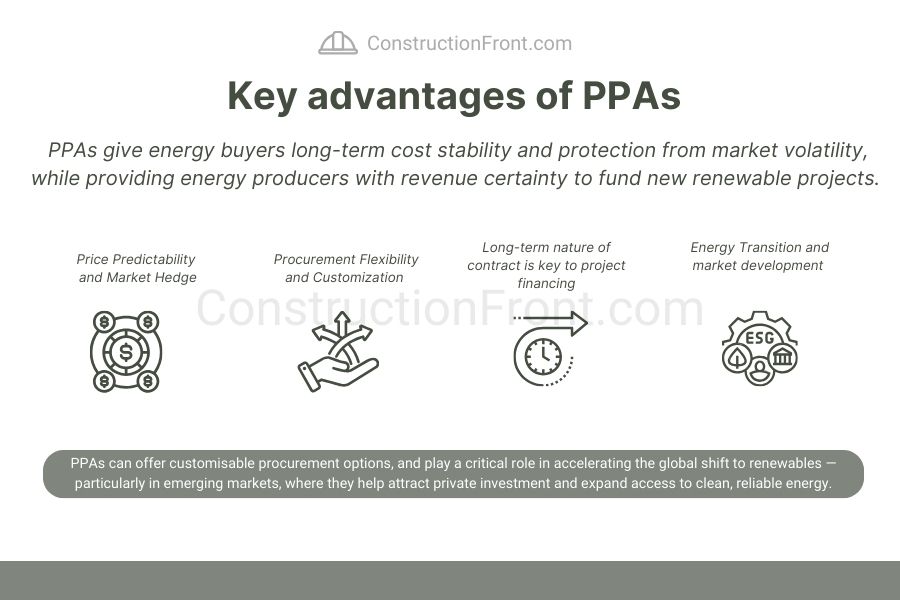

One of the key advantages of a PPA is that it allows energy buyers — including governments and large corporations — to manage long-term energy costs while hedging against volatile electricity markets. This is particularly valuable for energy-intensive industries, where supply reliability and price predictability are critical for long-term planning.

In parallel, PPAs provide energy producers with commercial certainty, enabling the development of new generation assets by securing future revenue. Key benefits of PPAs include:

- Predictability and market hedge: For buyers, PPAs offer a financial hedge against energy market volatility and future regulatory changes — such as rising retail tariffs or carbon pricing mechanisms. By locking in competitive rates, organisations can achieve long-term cost stability. For sellers, the guaranteed revenue stream mitigates market risk, supports cash flow predictability, and improves overall project bankability.

- Long-term project viability, bankability, and investor confidence: A secured offtake agreement significantly reduces revenue uncertainty for energy developers, helping them raise capital to fund project development and construction. This is particularly important for capital-intensive renewable assets like solar, wind, or hydropower, which require large upfront investment and long repayment periods. From a financier’s perspective, PPAs help de-risk projects and boost investor confidence.

- Procurement flexibility and customisation: PPAs can be tailored to suit a wide range of commercial and technical needs — including fixed or indexed pricing, phased delivery schedules, and flexible volume commitments. Depending on the structure, buyers may also benefit from features such as dispatchable supply, energy storage integration, and demand response capabilities, offering more control over energy usage and grid participation.

- Support for the energy transition and emerging markets: PPAs play a vital role in enabling the energy transition by facilitating private-sector investment in renewable infrastructure. In emerging markets, where access to public capital may be limited, PPAs help unlock private funding, improve access to reliable energy, and support local economic development — all while contributing to national sustainability and decarbonisation goals.

Common types of PPAs

As detailed above, PPAs offer some flexibility and customisation according to buyer and seller needs. There are various forms of PPAs, each designed to suit different commercial arrangements, technical contexts, and project scales. The most common include:

Type | Description | Typical Use Case |

Onsite PPA | Energy is generated at or near the buyer’s location (e.g. rooftop solar). | Commercial buildings, schools, warehouses with available space. |

Offsite PPA | Energy is generated at a remote facility and delivered via the grid. | Large corporates, institutions, or multi-site operators. |

Virtual / Synthetic PPA | Financial contract for difference (CFD) — no physical energy delivery, but buyer receives renewable energy certificates (RECs). | Corporations looking to offset emissions without managing physical delivery. |

Sleeved PPA | A retailer acts as intermediary between buyer and generator. | Entities without the scale or expertise to contract directly. |

Government-led PPA | PPA structured within public-private partnerships (PPPs) or procurement schemes. | Public infrastructure projects with energy needs and ESG mandates. |

The Relevance of PPAs for the Construction Industry

Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) are not only central to the financing and operation of energy projects — they also have direct and far-reaching implications for the construction industry. As developers pursue long-term offtake agreements to secure revenue streams, they simultaneously rely on the construction supply chain to deliver energy infrastructure on time, on budget, and to specification.

For construction contractors, PPAs represent a flow-on opportunity to participate in complex and large-scale projects such as solar farms, wind farms, waste-to-energy plants, battery energy storage systems (BESS), and hybrid microgrids. These projects require civil, structural, mechanical, and electrical works during the development phase, with increasing demand for contractors who understand the technical and commercial expectations embedded in PPA-driven projects.

In PPA-backed developments, construction outcomes have a direct impact on revenue generation. As such delays, underperformance, or defects can trigger financial and legal consequences under the PPA. As a result, energy developers are increasingly focused on transferring construction-related risks downstream through well-structured contracts — creating new pressures and expectations on contractors engaged in the sector.

PPAs and Construction Contracts

PPAs are typically signed at an early stage of a project’s lifecycle, often before financial close and construction procurement. For developers, aligning the PPA start date with project commissioning is critical — delays in energisation can trigger severe commercial penalties or revenue loss. To mitigate these risks, developers place strong emphasis on the construction strategy and contractual arrangements they adopt.

In most cases, developers subcontract the delivery of the asset to EPC (Engineering, Procurement and Construction) contractors, who assume full responsibility for completing the project on a turnkey basis. Under an EPC model, the contractor is accountable for design, procurement, construction, commissioning, and performance — offering the developer a single point of responsibility. This model is preferred by lenders and investors because it simplifies risk allocation and provides greater certainty over delivery and cost.

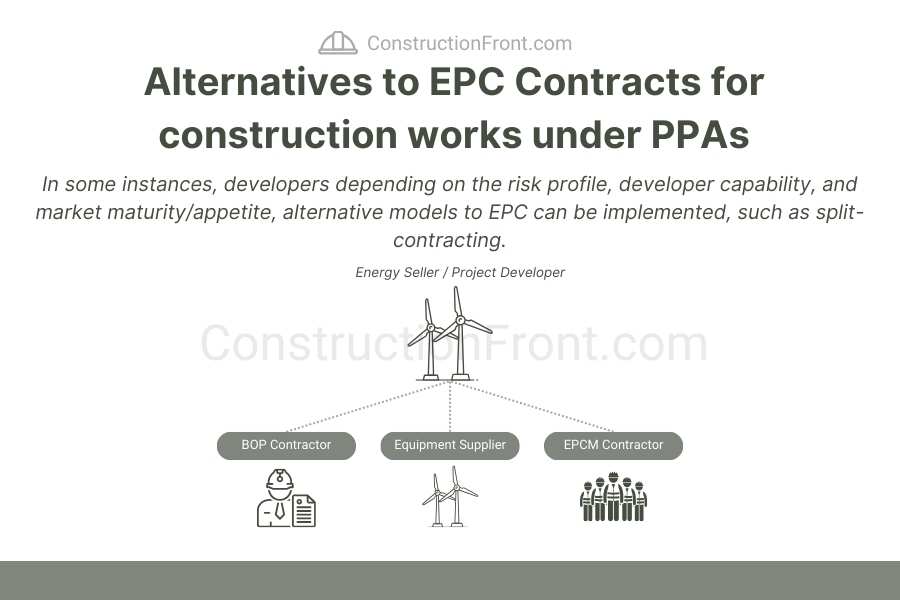

However, depending on the risk profile, developer capability, and market maturity, alternative models are also common. These include:

Split-contract arrangements, where the developer engages:

A Balance of Plant (BoP) Contractor for civil and electrical works, including grid connection, foundations, cabling, and substations;

A Main Equipment Supplier (OEM), such as a wind turbine manufacturer, solar panel supplier, or battery storage provider — often under a supply-and-install agreement;

An Owner’s Engineer or EPCM (Engineering, Procurement and Construction Management) provider to manage design, procurement, and interfaces on behalf of the developer.

- Multi-contract models, where several specialist contractors are engaged directly. While this gives the developer greater control over procurement and potentially better pricing, it also increases interface and delivery risks — making detailed interface management plans and robust coordination mechanisms essential. Therefore, it is only recommended for developers with significant expertise in project delivery.

- Consortium models or joint ventures, particularly in large-scale infrastructure or where international suppliers partner with local contractors to meet local content requirements or share technical capabilities.

Regardless of the delivery model chosen, there is a clear need to ensure that the construction contracts are “back-to-back” with the PPA obligations. This means that key dates (such as commercial operation date), performance bonds/guarantees (e.g. output, availability), and delay consequences must be mirrored downstream. This alignment ensures that if the construction contractor fails to deliver, the developer can enforce remedies and avoid defaulting under the PPA.

Key features and risks associated with Construction Contracts in the PPA environment

As discussed in the previous section, construction contracts are a foundational pillar in the successful execution of PPA-backed projects. Whether delivered under a turnkey EPC model or through a split-package arrangement involving a Balance of Plant (BoP) contractor and an equipment supplier, these contracts must be carefully structured to align with the obligations and risk profile established in the Power Purchase Agreement.

The PPA defines strict requirements for project delivery, performance, and availability, which in turn drive the key provisions and risk allocations embedded in the construction contract. A misalignment between these two documents can expose the project to significant commercial, legal, and financial consequences — from revenue loss due to missed Commercial Operation Dates (CODs) to default under the PPA or lender step-in.

The table below outlines some of the key critical features and risks typically associated with construction contracts in the PPA environment, illustrating how they are designed to support PPA compliance, mitigate project risk, and meet the expectations of financiers to enable financial close, offtakers, and other stakeholders.

Feature / Risk | Description and Relevance | Typical Contractual Mechanisms |

Time for Completion & Delay Risks | Timely completion is essential to meet the COD under the PPA. Delays can result in liquidated damages or termination by the buyer. | – Time for Completion clauses – Delay Liquidated Damages (DLDs) – Extension of time provisions for excusable events and time bar clauses |

Performance Guarantees | Output shortfalls or underperformance can reduce revenue or trigger penalties under the PPA. | – Performance testing regimes – Performance Liquidated Damages (PLDs) – Rectification obligations and step-in rights |

Security Instruments | Developers and lenders require assurance that contractors will meet delivery and performance obligations. | – Advance Payment Guarantees – Parent Company Guarantees – Retention or Bank Guarantees |

Defects Liability and Reliability | Ensures post-completion issues are corrected, maintaining long-term asset reliability critical to PPA compliance. | – Defects Liability Period (DLP) – Rectification at contractor’s cost- Access to plant data for performance tracking |

Interface Risk in Multi-Contract Models | When work is split between BoP and equipment suppliers, unclear scopes or delays by one party can impact project delivery and PPA timelines (i.e. equipment demurrage). | – Defined technical interfaces and milestones – Coordination protocols and EPCM support – Clauses managing interface delays |

Force Majeure and Change in Law | Long-term projects are subject to unforeseen events and regulatory changes, which can affect both construction and PPA delivery. | – Harmonised FM definitions in PPA and contract – Change in law provisions that allocate or share risk |

Alignment with Financing Requirements | Lenders require construction contracts that support stable and predictable revenue for debt repayment. | – Fixed-price, time-certain contracts – Step-in rights for lenders – Cure periods and defined termination triggers |

Examples of PPAs

Some real-world examples of PPAs are detailed below:

FAQ - PPAs

Virtual vs Physical PPAs - What is the Difference?

A physical PPA involves the actual delivery of electricity from the generator to the buyer, often requiring shared grid access. A virtual PPA (or financial PPA) is a contract for difference — no physical power is exchanged, but the buyer receives or pays the difference between the market price and the agreed price.

What is a step in right in a PPA?

A step-in right in a PPA allows a third party—usually a lender—to take over the project or contract if the energy producer defaults. This protects the buyer’s energy supply and helps secure financial and commercial close for project financing.

What is a cure period in PPA?

A cure period in a PPA is a set timeframe given to a party to fix a breach of contract before the other party can terminate or enforce penalties. It helps prevent immediate termination due to minor or fixable issues.

What is a Force Majeure Event in a PPA? Examples

A Force Majeure Event in a PPA is an unforeseen event beyond a party’s control that prevents them from fulfilling their obligations. It temporarily relieves affected parties from liability. Typical Examples are natural disasters (e.g. floods, earthquakes), war, pandemics, government actions, or major grid failures.

Need Help?

Do not hesitate to contact us (click here) for specialised advice in the construction industry.

Sources

Disclaimer: The articles on this blog are for informational and educational purposes only and do not constitute legal advice. While we strive to provide accurate and up-to-date information on construction law, regulations may vary by jurisdiction, and legal interpretations can change over time.