Traditional construction contracting and delivery approaches like Design-Bid-Build, EPC, or Design and Construct have long been the industry’s standard. However, they often leave teams working in isolation, with divided priorities and a tendency for disputes that often derail construction projects. To address these challenges, the industry has been moving toward more collaborative delivery models, such as alliance contracting.

Integrated Project Delivery (IPD) method is one of these models, gaining relevance in complex infrastructure and construction sectors. IPD emerged to address inefficiencies, fragmented decision-making, and rigid risk allocation in traditional models. But, what exactly is the IPD Method?

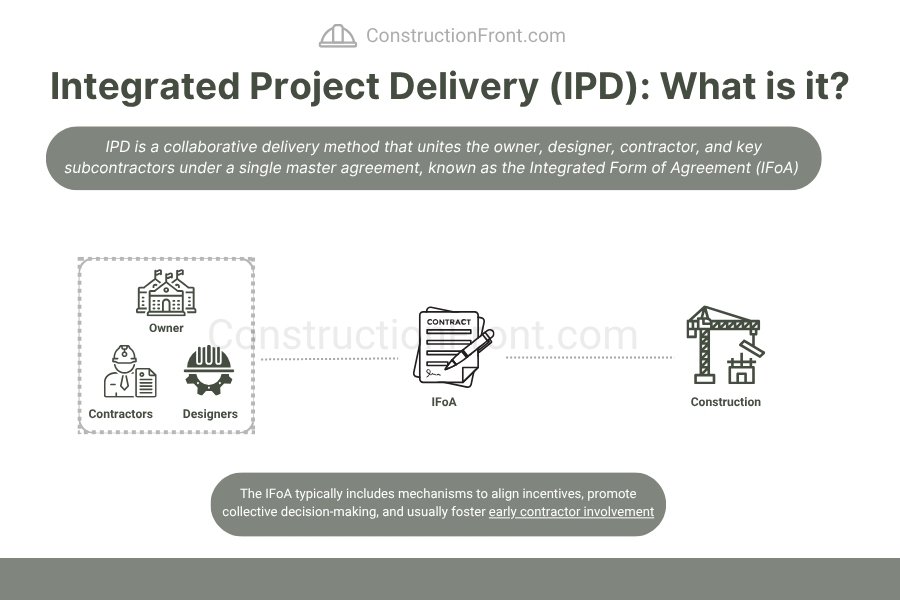

At its core, IPD is a collaborative delivery method that unites the owner, designer, contractor, and key subcontractors under a single master agreement, known as the Integrated Form of Agreement (IFoA). This agreement establishes mechanisms to align incentives, enable early contractor involvement, and foster collective decision-making. By creating a culture of trust and shared accountability, IPD significantly reduces risks of disputes, costly variations, and claims for delay or disruption.

This article unpacks what Integrated Project Delivery (IPD) is, how it works, what sets it apart, and how it compares to other delivery models. It also examines the types of projects where IPD is most effective, its key features, and the critical factors that can determine its success or failure

What is Integrated Project Delivery (IPD) method?

One of the defining features of the Integrated Project Delivery (IPD) method is its early and collaborative involvement of all key stakeholders—owners, designers, contractors, and often critical subcontractors—under a single master agreement, frequently referred to as the Integrated Form of Agreement (IFoA). This stands in contrast to traditional approaches, where parties operate under separate contracts and schedules, often leading to isolated efforts, communication gaps, and interface challenges.

Similar to alliance contracting, the IFoA typically includes mechanisms to align incentives, promote collective decision-making, and usually foster early contractor involvement. By establishing a framework for shared risk and reward, commonly referred to as pain-gain mechanisms, the IFoA encourages collaboration across all parties. This collaborative environment significantly reduces the risk of disputes, including variation requests, extension of time claims, disruption and delay issues, and potential claims for liquidated damages.

While risk-sharing, transparency, and collaboration form the heart of IPD, the actual structure of an IPD agreement can be adapted to fit the specific needs of each project and client. For example, some projects might adopt a tri-party agreement that includes only the owner, designer, and contractor, while others extend this to involve key subcontractors who play a significant role. Depending on the project’s scope and the owner’s preferences, key features may also vary, such as:

-

The exact mechanisms for sharing risks and rewards

-

The inclusion or exclusion of liability waivers and other specific clauses or mechanisms, such as time bars, early warning requirements, etc.

-

The stage at which IPD is implemented—whether during early design development or closer to project delivery

-

The choice of parties to be involved, ensuring that crucial subcontractors are included when their contribution is essential

-

Other bespoke elements tailored to meet the unique challenges and objectives of the project

This flexibility is what makes IPD a powerful tool for driving better outcomes and aligning interests across the entire project team.

When is the IPD method used?

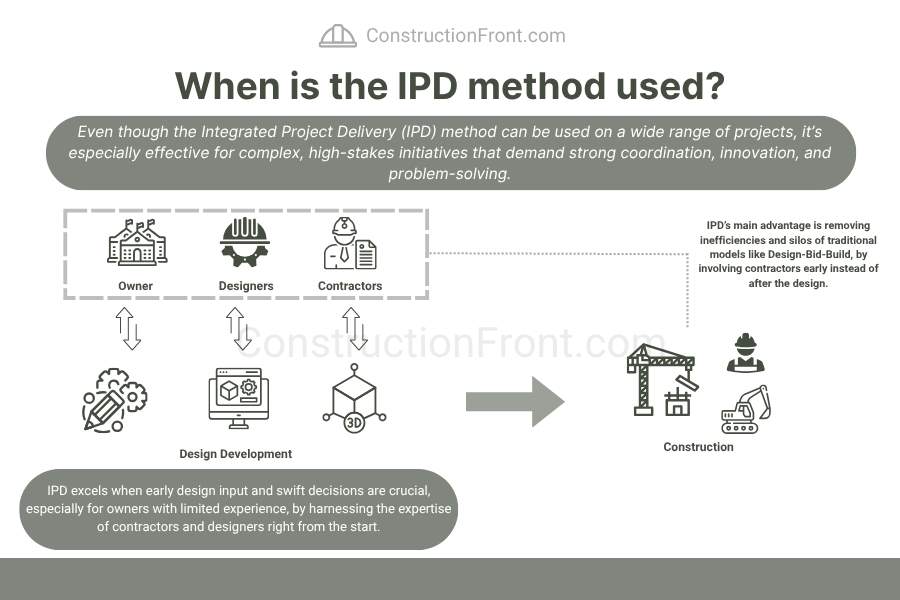

Even though the Integrated Project Delivery (IPD) method can be used on a wide range of projects, it’s especially effective for complex, high-stakes initiatives that demand strong coordination, innovation, and problem-solving. Examples include major infrastructure works, hospitals, airports, and other projects where design, construction, and stakeholder needs are deeply intertwined.

IPD is particularly valuable when early design input and rapid decision-making are critical to success. It’s also highly beneficial when the project owner has limited experience in developing and delivering large construction projects, as it enables specialist contractors and designers to contribute significant value early in the project’s development phase, similarly to a front-end engineering phase (FEED) for major industrial projects.

By involving the owner, designer, contractor, and often key subcontractors from the outset, IPD enables collective decision-making and ensures a holistic approach to project challenges. This early collaboration fosters open communication and alignment of priorities, allowing the entire team to identify potential issues, constraints, or conflicting requirements well before construction begins.

For example, on a large hospital project, early input from clinicians, facilities managers, and the construction team can ensure the design not only meets critical clinical needs but also accommodates practical considerations such as maintenance access, equipment installation, and patient flow. This shared understanding helps avoid costly design changes, rework, and construction delays that often arise when feedback comes too late or is siloed within separate team.

In essence, the early involvement of key stakeholders can lead to a more refined and buildable design, ultimately resulting in more effective construction and operation of the asset.

IPD’s main advantage is overcoming the inefficiencies and silos that often arise in traditional delivery models, such as Design-Bid-Build, where contractors typically enter the project only after the design is complete. In IPD, the entire team’s interests are aligned from day one, fostering an environment of innovation and proactive problem-solving. This shared accountability helps mitigate risks early and avoid costly variations, delays, or disputes.

What are the pros and cons of the IPD?

Like any delivery method, IPD has its strengths and weaknesses.

The benefits include improved project outcomes, reduced disputes, greater innovation through collective input, and a shared sense of ownership. On the flip side, the challenges of IPD can include the need for a cultural shift towards collaboration, potential legal complexities in drafting and negotiating the IFoA, and the risk that if trust and transparency aren’t fully embraced, the model’s full potential might not be realized.

Some of its pros and cons are detailed in the table below:

Pros of IPD:

-

Early Collaboration and Collective Decision-Making: By involving owners, designers, contractors, and key subcontractors from the start, IPD fosters open communication and alignment of goals. This early collaboration reduces the risk of costly design changes, rework, and delays.

-

Aligned Incentives and Shared Risks: Through mechanisms like pain-gain sharing, IPD aligns all parties’ interests, encouraging innovation, transparency, and joint problem-solving, which helps minimize disputes and costly claims.

-

Improved Efficiency and Reduced Waste: The integrated team approach often leads to more buildable designs, streamlined workflows, and better resource utilization, ultimately enhancing project efficiency.

-

Enhanced Risk Management: Shared accountability encourages proactive identification and mitigation of risks early in the project lifecycle, reducing surprises during construction.

-

Better Outcomes for Complex Projects: IPD is particularly effective for projects with intricate design and operational requirements—such as hospitals and infrastructure—where close coordination between disciplines is critical.

Cons of IPD:

-

Complex Contractual Arrangements: The Integrated Form of Agreement (IFoA) can be complex to draft and negotiate, requiring careful legal and technical input to balance interests fairly.

-

Cultural Shift and Trust Requirements: IPD demands a high level of trust and collaboration that may be unfamiliar or uncomfortable for parties used to traditional contracting models. Establishing this culture can take time and effort.

-

Limited Suitability for All Projects: IPD may not be ideal for smaller or less complex projects where the cost and effort of integration might outweigh the benefits.

-

Potential for Ambiguity in Roles: With multiple parties working closely together, there can be challenges in clearly defining responsibilities, which, if not managed well, could lead to confusion or conflict.

-

Early Commitment Needed: Because IPD relies on early involvement of contractors and key subcontractors, owners must commit to the delivery method early, which may be difficult in projects with evolving scopes or budgets.

Key Success Factors and Challenges in Implementing IPD

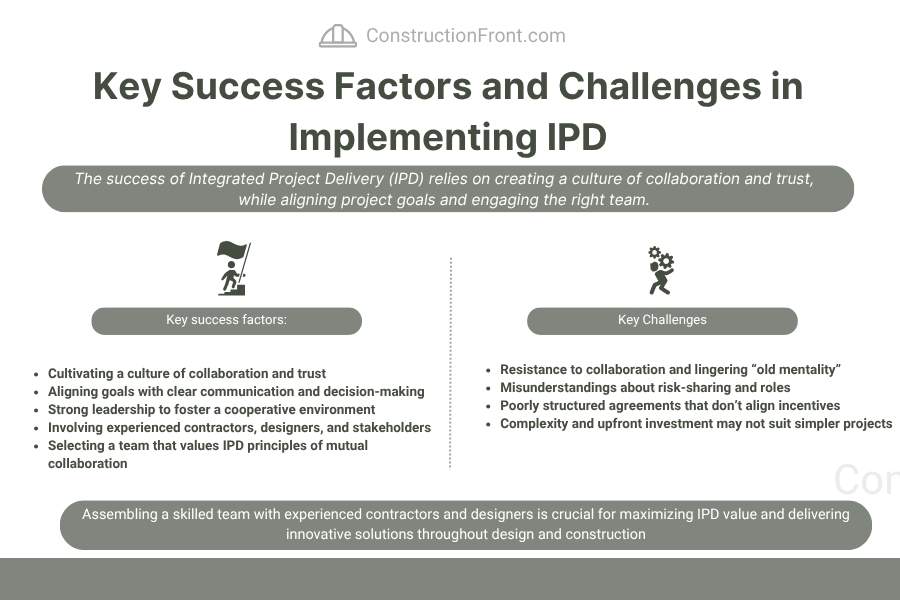

The success of IPD hinges on several critical factors. A culture of collaboration and trust is fundamental—without it, even the most robust contracts are unlikely to achieve the intended outcomes. Clear, aligned goals, reinforced by effective communication and transparent decision-making, are equally essential. Strong leadership is crucial in fostering these behaviors and promoting a cooperative environment.

However, another important success factor is assembling a project team that includes experienced contractors, designers, and key stakeholders who can provide valuable insights and actively drive value engineering during both the design and construction phases. Their expertise helps unlock the full potential of IPD, leading to better project outcomes and more innovative solutions.

From this perspective, selecting the right project team is critical. Owners should consider not only the team’s proven track record in delivering similar projects but also whether their corporate culture embraces the IPD principles of mutual collaboration and trust.

Challenges in IPD often arise from resistance to collaboration, misunderstandings about risk-sharing mechanisms, or misaligned expectations and unclear roles. Teams unprepared for this new contract approach—often holding on to an “old mentality” that seeks conflict rather than cooperation—can also undermine the benefits of IPD.

To address these challenges, the Integrated Form of Agreement must be carefully structured to fairly incentivize all parties and promote equitable risk-sharing. Key contractual elements often include clearly defined pain-gain share provisions, effective dispute resolution processes, early warning mechanisms, and robust contingency management principles, such as clear methodology to manage the program float.

While IPD can deliver superior outcomes, it’s not suitable for every project. It works best when clients and teams prioritize collaboration and transparency and when the project’s complexity and scale justify the upfront investment in aligning interests. For simpler or smaller projects, the added complexity of IPD may not provide a commensurate return.

Practical Examples of IPD - UCSF Medical Center at Mission Bay in San Francisco

To illustrate how Integrated Project Delivery (IPD) works in practice, consider the UCSF Medical Center at Mission Bay in San Francisco—a landmark example of IPD in action. This $1.5 billion, 878,000-square-foot facility comprises three specialty hospitals: Benioff Children’s Hospital, Bakar Cancer Hospital, and Betty Irene Moore Women’s Hospital.

The project was delivered using a public-sector-adapted IPD model, which fostered deep collaboration among the owner, designers, contractors, and key subcontractors from the outset. A notable feature of this project was the establishment of the Integrated Center for Design and Construction (ICDC), a co-located workspace where over 250 team members worked side by side.

This setup enhanced communication, expedited decision-making, and cultivated a unified team culture focused on patient-centered outcomes. Despite incorporating $55 million in design changes and variations during construction, the project was completed eight days ahead of schedule and came in under budget by approximately $200 million compared to traditional delivery estimates.

The UCSF Medical Center at Mission Bay exemplifies how IPD can drive innovation, efficiency, and superior outcomes in complex healthcare projects – see project construction time-lapse below – courtesy of UCSF.

Conclusion

In an industry that often grapples with fragmented teams and misaligned interests, Integrated Project Delivery (IPD) offers a refreshing, people-centered approach. By bringing together owners, designers, contractors, and key subcontractors from the start, IPD creates a shared sense of purpose and trust that’s crucial for tackling the complexities of modern projects. It’s not just about better outcomes on paper—it’s about fostering a culture of collaboration and innovation that can make the work more rewarding for everyone involved.

Of course, IPD isn’t for every project or team. It demands a willingness to embrace new ways of working, and to build relationships based on transparency and mutual respect. But when those pieces come together, as they did for the UCSF Medical Center at Mission Bay, the results can be remarkable: projects delivered faster, at lower cost, and with fewer disputes. In the right setting, IPD isn’t just another delivery model—it’s a smarter, more human way to build.

Need Help?

Do not hesitate to contact us (click here) for specialised advice in the construction industry.

Sources

- LEAN PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT AT CATHEDRAL HILL HOSPITAL PROJECT

- Transitioning to Integrated Project Delivery: Potential Barriers and Lessons Learnt

- Comparative analysis between integrated project delivery and lean project delivery

- Integrating Project Delivery – Martin Fischer, Howard W. Ashcraft, Dean Reed, Atul Khanzodes

- Integrating delivery of a large hospital complex – Internation Group for Lean Construction

- University of California San Francisco, Medical Center at Mission Bay | HFM Magazine

Disclaimer: The articles on this blog are for informational and educational purposes only and do not constitute legal advice. While we strive to provide accurate and up-to-date information on construction law, regulations may vary by jurisdiction, and legal interpretations can change over time.